📡 详细介绍

☀️ 操作攻略

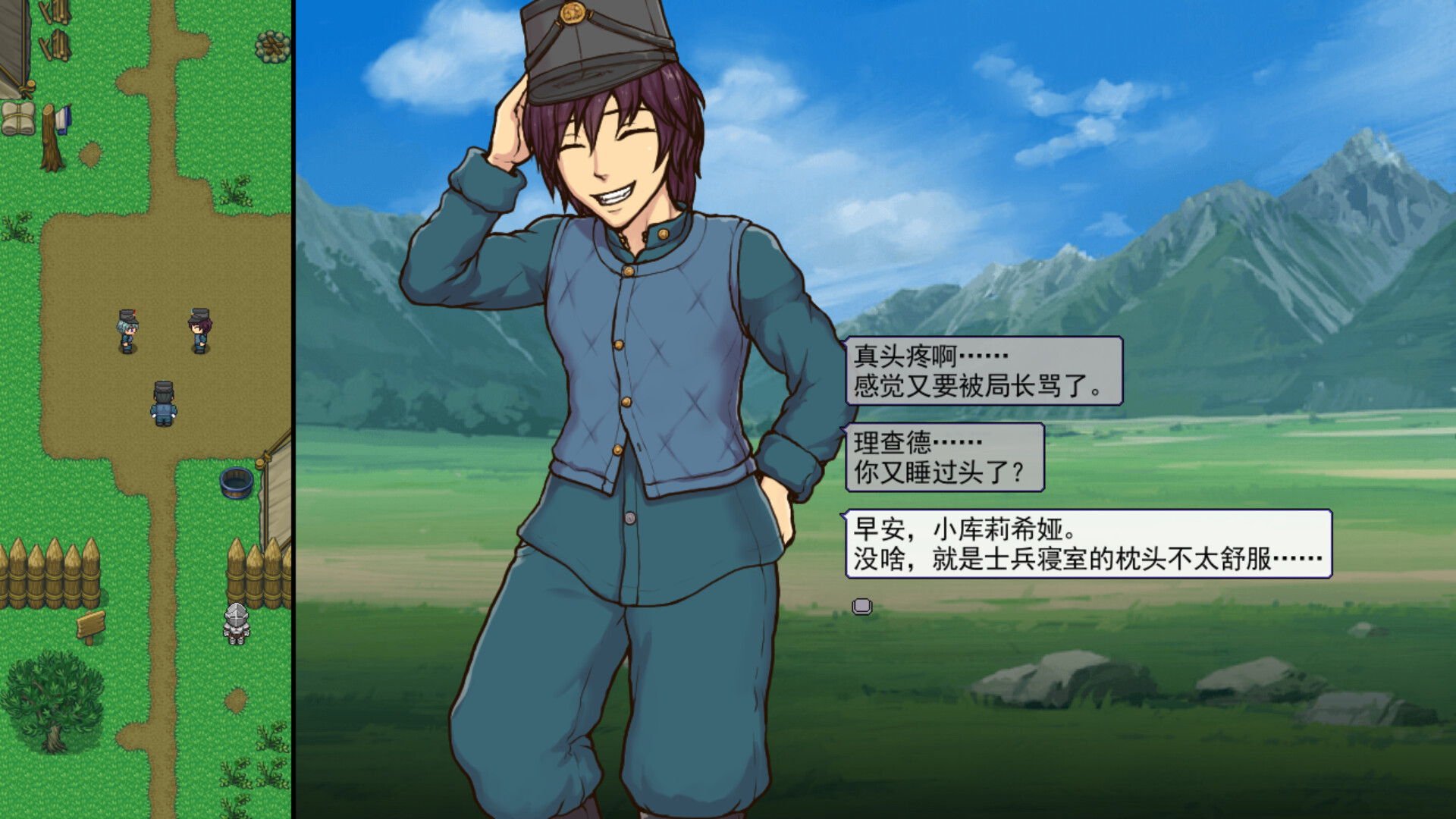

名称: 帝国入境所

类型: 冒险, 独立, 角色扮演

开发者: Tengsten

发行商: Kagura Games

系列: Kagura Games

发行日期: 2022 年 9 月 3 日

关于此游戏

兵长提尔在大统一战争中出色的表现为他赢得了“长枪使提尔”的美称,他的功勋和威名在军队中无人不知晓,无人不称赞。所有人(包括他自己)都以为他会在战争结束后一路升官,在军队中担任要职,但他最后却被莫名其妙地调度到了刚刚成立的国家安全局。国家安全局的局长奥莉维亚·里德尔解释说这是因为世界在变化,只懂得舞刀弄枪的武夫终将被时代淘汰,他们的位子也会被踏实勤恳的文职人员所取代。出于服从命令的军人天性,提尔接受了这一任命,成为了新帝国的一名入境检查官,但他很快就发现,这份工作并不像他想象得那么单纯……作为边境检查站的检查官,您的职责是对每一个想要通过检查站的旅客进行检查,确保他们的文件不存在问题,入境理由也合理可信。但旅客们手中的文件可并不简单,您需要逐一核对文件上的日期,照片以及各种信息,只要有一项不符合标准,您就必须将这位旅客拒之门外。另外,您每天的工作时间是有限制的,而您能获得的报酬取决于您在这段时间内正确检查的旅客数量。也就是说,您既要在规定的时间内检查尽可能多的旅客,又要保证在检查时不犯下差错。随着剧情的推进,您将会获得晋升至更高级别的检查站的机会,但如此一来检查时的条条框框也会逐渐增加。如果您想要维持稳定的收入,那就必须眼尖心细,不放过文件上的任何一个可疑之处。此外,一些极端分子还会在入境时随身携带危险物品,所以如果有必要的话,您需要亲自制服这些极端分子,妥善地处理这些危险物品。

您也可以利用您的工资从旅行商人手中购买各种能够提高检查效率的工具。无论是能瞬间检测出违禁品的金属探测仪,还是能够降低旅客们压力的焦虑缓解香水,都能为您的工作打开一扇扇便利之门!

帝国入境所之所以体验入境检查官的工作在您的入境检查官生涯当中,您会遇到形形色色的通行者,而您的职责就是在迷你游戏当中检查他们出示的每一份文件,并将这些文件与旅客的说辞进行核对。如果您觉得工作过于繁琐,那么您也可以使用工资购买各式各样的道具,让工作的流程变得更加简便。只要您能够将不符合规章制度的旅客拒之门外,并且把危险分子绳之以法,那么升迁则指日可待!

随机生成且特色各异的NPC

每一名旅客都是由系统随机生成的,以便在每一轮游戏当中为您提供独一无二的游戏体验。此外,有一部分特殊NPC还拥有专属的背景故事,并且会在特定的条件下为您开启专属的支线剧情。当然了,并不是所有旅客都是安分守己的好公民。将心怀不轨,想要危害帝国安全的凶徒捉拿归案也是您的责任的一部分。

具有高度交互性的游戏世界

您在游戏过程中遇到的每一位NPC,到达的每一个地点,和必须遵循的每一项规章制度都会为之后的剧情埋下伏笔,而您对待这些人事物的态度则会影响整个剧情的走向。如果你在工作中表现得从容得体,您就会成为能令长官们刮目相看的才俊;而如果您对于各种细节观察入微,您说不定就能发现国家安全局深藏不露的秘密……

成人内容描述

开发者对内容描述如下:

The Imperial Gatekeeper contains strong language.

系统需求

最低配置:

操作系统 *: Windows® 7/8/8.1/10

处理器: Intel Core2 Duo or better

内存: 4 GB RAM

显卡: DirectX 9/OpenGL 4.1 capable GPU

DirectX 版本: 9.0

存储空间: 需要 50 MB 可用空间

附注事项: 1280x768 or better Display. Lag may occur from loading menus or maps. Turn off other programs before running the game.

推荐配置:

操作系统 *: Windows® 7/8/8.1/10

处理器: 2+ GHz Processor

内存: 4 GB RAM

显卡: OpenGL ES 2.0 hardware driver support required for WebGL acceleration. (AMD Catalyst 10.9, nVidia 358.50)

DirectX 版本: 9.0

存储空间: 需要 4 GB 可用空间